The Fallon Story

TWIN CITIES BUSINESS MAGAZINE – Advertising agencies do creative work. They are staffed with “creatives.” And the lobby of Fallon’s downtown Minneapolis office is designed to leave no doubt that one has entered a creative environment.

TWIN CITIES BUSINESS MAGAZINE – Advertising agencies do creative work. They are staffed with “creatives.” And the lobby of Fallon’s downtown Minneapolis office is designed to leave no doubt that one has entered a creative environment.

The legendary ad shop originally known as Fallon McElligott Rice returned to the AT&T Building at Ninth and Marquette in 2008, after expanding into bigger quarters downtown in 2001. A smaller Fallon now occupies three floors that were redesigned to striking effect: a reception area floored in what seems like an acre of hickory—unexpected underfoot in a modern office tower; lobby sofas and chairs in red and orange paisleys; a cube-like fireplace; a coffee bar; and those retro, Empire State Building–style viewing scopes for visitors inclined to investigate the sights visible to the north through floor-to-ceiling windows.

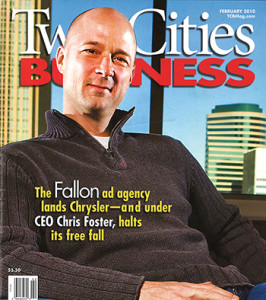

Not a bad place to come to work everyday, observes Fallon CEO Chris Foster. Lately, coming to work has been a more cheerful experience.

When Foster arrived in March 2008, his job was not so much to assume the throne at a firm long regarded as one of the most creative in its field as to stop the bleeding and restore faded luster.

Since losing BMW in 2005, one of the agency’s top priorities has been to land another automobile account. Now, at last, Fallon has a car.

Foster and others have been virtually certain since October that Fallon would become the lead agency of record for the Chrysler Group’s namesake brand. The official announcement didn’t come until December, but activity behind the scenes was furious through the autumn months.

“When you’re transitioning a piece of business on this scale,” says Fallon’s chief marketing officer Rob Buchner, “there are a lot of moving parts.” Once the news was public, the agency began recruiting openly for roughly 30 new positions. Pre-Chrysler, Fallon employed just under 200 in Minneapolis and just under 500 globally. Fallon has offices in Minneapolis, London, and Tokyo.

Buchner says the new account might be the largest ever brought into the Twin Cities. Even after a steep drop in 2009 car sales and ad budgets, Chrysler is expected to spend well over $200 million on advertising in 2010. (That includes not only fees to Fallon, but the cost of air time for television ads and other expenses.) Fallon built former client CitiBank into a $400 million account, Buchner says, “but when we took over in 1999, it was a fraction of that.” Chrysler’s ad spending has reached $500 million, in years past, suggesting potential for growth if the brand recovers.

Billings from Chrysler will boost Fallon’s revenues by 25 or 30 percent, Foster says. He doesn’t disclose what 2009 revenues were.

Chrysler is the great white shark, but it’s not the only fish Fallon has landed since Foster left his executive vice president post at Saatchi & Saatchi in New York—a sister agency that’s also owned by Publicis Groupe of Paris—to take the reins at Fallon. Others include Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank, General Mills’ Totino’s brand pizzas and pizza rolls, Boston Market, Nestlé Beverages, Nestlé’s Alpo brand dog food, cable-TV company Charter Communications, and Beam Global’s Cruzan Rum.

By the time Fallon landed the Cruzan account last July, Advertising Age cheered the win as “the latest evidence that the agency is pulling out of a harrowing freefall.” If Fallon can hang onto its year-to-year contract with Chrysler, the recovery would appear to be cemented.

“Ask me in six months”

Foster objects to the word “freefall,” but he does allow that for the past four years, Fallon had been in a “contraction phase.” The agency added Sony to its client list in 2005, and has retained its business with Holiday Inn, NBC Universal, the Travelers Companies, Time magazine, and others. But it was badly wounded by an exodus of major accounts. Between 2005 and 2007, Fallon lost Lee Jeans, BMW, Dyson vacuums, United Airlines, and Citibank.

In 2006, Fallon was still the second-largest ad agency in the Twin Cities, with annual revenue estimated by Ad Age at $62.2 million, trailing only long-time market leader Campbell Mithun. By 2008, revenue had dropped to an estimated $41.6 million, and Fallon ranked fourth in the market, behind Campbell, Carmichael Lynch, and Periscope.

Last year, Foster radically redrew the organization chart, collapsing some 17 departments into three. In July, he installed Darren Spiller, from Publicis Mojo in Australia, as chief creative officer. Foster says this will at last put a stop to the game of musical chairs in Fallon’s top creative role. Spiller brought along Mojo art director Christy Peacock to serve as head of design. Her addition brings back in house a function that had been outsourced, mainly to Duffy & Partners, a former Fallon unit that was spun off in 2004.

“Are we 100 percent back?” Foster asked rhetorically after the Chrysler win was announced. “Ask me in six months.” Fallon has “great stuff” coming in 2010 for Travelers, one of its biggest accounts, he says. Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank and other clients also will launch more vigorous ad campaigns. Then there’s Chrysler. “By mid-year 2010, we’ll have a lot of stuff out there.”

Fallon is poised for a growth spurt that will enable it to reclaim its global status as a creative powerhouse, Foster believes. Many of his Twin Cities competitors say they’re rooting for him. And they appear quite sincere.

The Legacy: “Great creative doesn’t have to come from New York”

Fallon McElligott Rice was launched in 1981 on the avowed principle that advertisers should outthink their rivals, not outspend them. A founding belief, asserted in a full-page newspaper ad announcing the agency’s birth, was that “imagination is one of the last legal ways to gain an unfair advantage over your competition.” (Cofounder Pat Fallon would expand on that assertion in later years, including in the 2006 book he co-authored, Juicing the Orange: How to Turn Creativity into a Powerful Business Advantage.)

Over the next two decades, Fallon became one of the world’s top shops for television and print advertisers seeking big-impact campaigns that would create buzz for their brands. It was Fallon that put army helmets on Gold’n Plump chickens in the 1980s and parachuted them into battle to protect Minnesota from an “invasion” of southern poultry. Awards and accolades piled up for other memorable ad campaigns, such as the EDS “cat-herders” commercials in 2000 and, more recently, Citibank’s “live richly” and “identity theft” campaigns.

In the process, Fallon put Minneapolis on the map as a world-class advertising center. “I hardly even know Pat Fallon, but I will be forever grateful to them for their impact on this market,” says Greg Kurowski, president and CEO of Minneapolis-based Periscope. “They brought an aura of creativity that had never been here at that level.”

“Fallon brought a lot of national attention to the [Minneapolis] ad market. That’s good for everybody,” says Campbell Mithun CEO Steve Wehrenberg. In the 1980s, “when Campbell was the only big game in town,” he says, it was much harder to recruit talent from New York or Chicago, never mind other countries. People figured that if things didn’t work out at Campbell, or if their client left the agency, they’d have to pack up their families and move again.

Today, thanks in large part to Fallon, there are a number of sizeable agencies in town making up a bona fide market, Wehrenberg says. Fallon alumni are plentiful in it. He points to Carmichael Lynch CEO Mike Lescarbeau as a notable case in point.

Several ex-Fallonites have further expanded the market by founding their own Twin Cities firms in the past six years: Michael Hart of branding agency Mono; former Fallon president Rob White of marketing agency Zeus Jones; Bruce Bildsten and Michelle Fitzgerald of “Brew: a Creative Collaborative”; and Bob Barrie and Stuart D’Rozario, who landed the United Airlines account shortly after they left Fallon in 2007 to form Barrie D’Rozario Murphy.

Fallon’s impact on the ad world’s center of gravity extended beyond the Twin Cities. It was one of a handful of agencies responsible, in the 1980s and 1990s, for proving that “great creative doesn’t have to come from New York,” says Advertising Age reporter Jeremy Mullman. “Marketers all over the world wanted them.”

Asked to name the hottest creative shops of the moment—“today’s Fallons”—Mullman and other sources rattled off the same three names: Crispin Porter & Bogusky, with offices in Miami and Boulder, Colorado; Goodby Silverstein & Partners of San Francisco; and Wieden & Kennedy of Portland, Oregon. Crispin Porter was among the agencies competing with Fallon for the Chrysler account.

None of those three are in New York or Chicago, Mullman notes. “Fallon was one of the agencies that proved you didn’t need to be.”

What is, or was, the Fallon mystique, exactly? “‘Edgy’ is an overused term in this industry,” says Brew’s Bruce Bildsten, who had been with Fallon 21 years when he left in 2005. “Our heritage was about doing things bigger and bolder. Everything Fallon did was big, bold, and smart. But it was often smart and elegant, not edgy.”

Pat Fallon and his partners sold their agency to Publicis in 2001 for a reported price of about $140 million. Fallon stayed on as chairman and CEO. But in 2007, with the Minneapolis operation struggling, Publicis grouped Fallon Worldwide with Saatchi & Saatchi in a holding unit called SSF. Both companies began reporting to Saatchi Worldwide CEO Kevin Roberts in New York. Pat Fallon’s title changed to chairman emeritus.

He declined to be interviewed for this story, but Fallon is still present at his namesake firm. “He’s in here three or four days a week,” says CMO Buchner. “He’s the keeper of our culture in a lot of ways . . . . He’s just not burdened with the operations of the company, and he’s not busting his butt on airplanes in the same way he did for 35 years.”

“It’s a different world from the one Fallon thrived in”

By all accounts, from inside and outside the agency, the reasons for Fallon’s slide had nothing to do with dwindling creative prowess. The agency still has plenty of talent, and its recent work for clients such as the Ladders and Travelers Insurance continues to draw admiration.

Observers point instead to three problems that plagued the agency in recent years. One was a simple run of bad luck. BMW, Dyson, and Citibank all were lost following management shakeups at the client end. New marketing managers are notorious for cleaning house and bringing in their own favored agencies, regardless of what an incumbent agency has done.

An internal handicap was rapid turnover in the top creative director spot. After longtime executive creative director David Lubars left the agency in late 2004 for BBDO in New York, Fallon churned through five different creative heads in less than five years. Three of the departures were attributed to a lack of “cultural fit.”

Finding the right creative leader was Foster’s top strategic priority. He insists that Spiller is at last the man for the job: “I went to the most creative pockets around the world to try to find talent, and Darren emerged head and shoulders above everybody.”

Spiller was instrumental in landing the Chrysler account, Foster says. “In the vision we presented to Chrysler, he was the leading voice . . . . He’s got the right sensibilities: a great sense of style, a sense of international business, and a very adaptive, responsive demeanor with clients. That really helped us work with these guys.”

Spiller, who handled accounts including Nike and Nestlé when he ran Mojo’s Australia and New Zealand operations, says that he, like Foster, had long admired Fallon’s work. The cultural-fit problems said to have plagued predecessors don’t worry him.

“I think I understand the values of the Midwest,” Spiller says. “You say it how it is, you be polite, you don’t go out of your way to treat people badly, you take time to explain things to people . . . . I just kind of get the place, really.”

Several sources outside Fallon say that a third reason for the agency’s recent problems has been slowness to adapt to a changing marketing climate.

As Mullman puts it, “There have been massive changes in consumer behavior, the things people read, what they watch, and how, and when. Fallon got famous for TV spots. Now Tivo skips them.”

Television advertising is still very much with us, but it attracts a shrinking percentage of marketing dollars. “It’s a different world from the one Fallon thrived in,” says former Fallonite Michael Hart, creative co-chair at Mono. The new media landscape requires agencies to operate with a kind of seamlessness that demands a different organizational structure, he says. “The walls between design, interactive, advertising, and social media need to be taken out.”

The charge that Fallon has been slow to adapt to changes wrought by the Internet is ironic, and underscores the pace of change. As recently as 2002, the agency’s BMW Films series was heralded as a groundbreaking use of online media. The short films, directed by the likes of John Woo and Ang Lee, paired BMWs with marquee names including Clive Owen, Madonna, and blues legend James Brown, and were glossier and more ambitious than anything Web advertisers had done before—or probably since.

“I’m not trying to make Fallon what it was”

Without acknowledging any industry perception that Fallon was a TV-centric shop that didn’t quite get new media or “seamlessness,” Foster has made a number of moves that seem intended to dispel those concerns.

Last March, Fallon released a free, downloadable “lifestreaming” application called Skimmer, which consolidates on a computer’s desktop the feeds from social networks including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. The agency announced that in giving away the application, it was demonstrating a philosophy of “generosity” that it preaches to clients. But the gesture also clearly was meant to demonstrate Fallon’s intimate familiarity with social media.

As for seamlessness, just as the design function was reintegrated into the firm under Christy Peacock, Fallon Interactive, the in-house digital unit, was absorbed along with other departments in Foster’s reorganization. “Interactive is kind of baked into everything we do,” he says. “We have an interactive person pretty much on every team. We don’t treat it as a separate discipline.”

His approach to restructuring has been to identify a few core functions and then merge all of the departments that have those responsibilities in common. “For an agency with a little less than 200 people [in Minneapolis], 17 department heads is a lot,” Foster says. “We basically said there are three key functions here, and that’s how we organized ourselves.” He calls the new units Insight, Development, and Activation.

Insight includes planning functions—account planning, creative planning, data analysis, and connection planning—that is, connecting a brand to consumers’ lives.

Development, under Spiller, includes creative, media, digital, and design work. As Foster explains it, “‘Insight’ is the guys who develop the intellectual property and the consumer understanding. ‘Development’ is the guys who actually make the stuff.”

Activation, headed by Chief Operating Officer Mike Buchner (brother to CMO Rob Buchner), includes “people who make the stuff happen—account service, production, project management,” Foster continues.

Rob Buchner says that the newly integrated structure helped Fallon win the Chrysler account and present the right face to the car company’s decision makers. “They’d have a hard time delineating between our digital thinkers, our social media thinkers, and our core creative people,” Buchner says. “We’ve got everybody converging on the same problem.”

Spiller is onboard with the media-blending talk, and more blunt about the issue of TV-centricity. “Fallon was one of the best TV agencies, if not the best, in the world,” he says. “But now you can’t be good at one thing. You have to be good at a lot of things to survive in this industry . . . . I’m not trying to make Fallon what it was. I’m trying to make it something new.”

“We need clients who are willing to stick their necks out”

Foster says his top priorities for the agency are “creativity and growth—the same as everyone else’s.” During the reorganization, he set up a special new-business unit under CMO Rob Buchner—not quite amounting to a fourth “department”—to pursue new accounts or expand Fallon’s reach into existing ones.

Top goals under the new-business heading were to land a car account and a financial institution. “As the economy gets into recovery, those will be the big-spending categories and the ones that will need the most help,” Foster says. One down, one to go.

A third target category is packaged goods. Rob Buchner says Foster’s experience with Procter & Gamble was helpful in winning the Totino’s account from General Mills. Spiller’s background with Nestlé adds additional packaged-goods credibility.

“I’d like to think we’re just at the beginning of a turnaround,” Foster says. He admits that obstacles are plentiful. The economy is still shaky, which means that advertisers are still frightened and are holding back on spending.

“If we believe in the unlimited power of creativity, we need clients who are willing to stick their necks out,” he says, “clients who believe that creative transformation has a multiplier effect on a business.”

One place to find them could be in troubled sectors like the automotive industry and troubled companies like Chrysler. If the recession is officially over—and Fallon’s slump is, too—this economy still offers up plenty of brands that must do something dramatic to pull out of a downward spiral.